Twisted, Stamped & Swirled: The Pastas of Liguria

Twisted, Stamped & Swirled: The Pastas of Liguria

New York-based cook, food writer and author Andy Baraghani pens an ode to the pastas of Liguria, celebrating the little things that make his five favourite shapes particularly special.

I overthink every detail of my cooking, which is why I probably agonise over picking the perfect pasta shape more than most people. But I swear, there’s good reason. As a cook and a pasta lover, deciphering which pasta shape to choose pushes me to the brink of a migraine (then again, so does picking out a TV show). Distinctions among the hundreds–some say well over a thousand–of pasta in Italy have mostly to do with their geometry.

Over centuries, every region in Italy has developed its own shapes featuring unique contours, ridges, diameters, and lengths–characteristics that lend themselves to specific sauce applications. There are the obvious ones: bucatini, strawlike from Lazio, is most famously paired with a spicy red sauce made with guanciale, chiles, and pecorino; tiny beads known as fregola are cooked gently with tomatoes and seafood; ear-shaped orecchiette from Puglia get tossed with bitter broccoli rabe and garlic. Liguria, one of the smallest of the 20 regions, may boast one of the most famous sauces of Italy–pesto–but the pastas in the area deserve just as much of the spotlight.

I find myself not in Liguria but in my city kitchen in New York, staring into a pantry of mismatched pasta shapes. I’ll spend too much time considering how they’ll complement the pesto I’m making and then spend too much time deciding what to listen to while I cook. But that’s the point. This is time worth taking. A few simmering minutes later, I’ll surrender myself to one of life’s greatest pleasures: eating a big bowl of pasta. On the following spread you’ll find five shapes to seek out next time you’re at an Italian market or restaurant. Better yet, you can use them as an excuse to fly to Liguria.

Illustrations by Sofia Iva

Illustrations by Sofia Iva

TROFIE

Trofie may be the most famous shape to come out of this region. Its origin story is unclear, but one idea is that the shape was created by mistake. After a cook finished making pasta dough, they wiped their hands of any leftover dough scraps and out came a twisted, scraggly piece of pasta. The fresh, eggless dough is made with wheat flour, water, and salt. Its short, ropelike shape has these nice nooks and crannies that help trap whatever sauce it’s married with. It falls under the category of short pasta, a broad field that includes gemelli, fusilli, and farfalle, to name a few. These shapes allow you to stab them with a fork, rather than twirl. I like to use short kinds of pasta with other ingredients that can stack onto the fork with them, such as crispy artichokes, leafy greens, or canned tuna.

CORZETTI

Corzetti of Liguria are small, stamped-out coin-shaped pastas. They have a close cousin from the Piemonte region, also eaten in Emilia-Romagna, that goes by a similar name. Born during the Renaissance era, these pasta shapes were used by noble families to showcase their coat of arms through stamping pasta. While that is very much not the case today, you’ll still see imprints of suns, trees, or flowers. The shapes are embossed with a special wooden stamp that gives them a subtle texture for the sauce to cling to.

TRENETTE

While trofie and corzetti have unique identifiers, the long, flat trenette is easily mistaken for linguine, but it’s actually a touch wider. The long strands are often difficult to find outside of Liguria compared to other flat pasta, like linguine or fettuccine. Trenette is often served with pesto, usually alongside rough-cut boiled potatoes and blanched green beans. It’s an extra-starchy plate that may require both a knife and a fork and then a nice nap.

Illustrations by Sofia Iva

Illustrations by Sofia Iva

PANSOTTI

Pansotti are ravioli’s bell-shaped cousins. Dumpling-like, their dough can be quite thin and almost transparent, revealing the ricotta and wild greens that fill it. Traditional recipes call for the wild greens to be dandelion, stinging nettles, borage, or chicory, but cultivated greens such as spinach are also often used. You’ll find pansotti in and around osterias in Liguria served with salsa di noci, a ground walnut sauce made with bread, milk, and cheese. A spoonful of pesto would also do you good–just try to avoid drowning pansotti in an overly rich meat or tomato sauce that would overwhelm the delicate filling within.

MANDILLI DE SAEA

Apologies to any Italians reading this, but mandilli de saea (Genovese for silk handkerchiefs), are just delicious pasta blankets. Unlike other pastas in the region, this dough often has egg added to it, giving it a smoother, silkier, quality. Because mandilli de saea is always cooked fresh, I find it slightly tricky to cook with, and don’t even think about draining this pasta in a colander as all the pieces will stick together. Instead, boil the pasta for 2–3 minutes, and use tongs to transfer it directly to a pan with your sauce. It’s wonderful when stained with pesto, but I love it with a rich ragu because it emphasises the blanketlike quality of the pasta, giving the whole dish a feeling of luxurious comfort. The sheets are also ideal for baked pasta dishes where they function like shorter sheets of lasagne noodles with a more rustic aesthetic.

Andy Baraghani is a cook, food writer, and the author of The Cook You Want To Be: Everyday Recipes to Impress. Andy lives in New York City with his extensive mortar and pestle collection.

This article is taken from Belmond’s new cookbook on Liguria, in partnership with Apartamento and available to purchase now: LIGURIA: Recipes & Wanderings Along the Italian Riviera © 2024 Apartamento Publishing S.L.

For more tastes of the Italian Riviera, check out our three Youtube recipe films shot with Andy on locations in Portofino.

Illustrations by Sofia Iva

Delve deeper into

You might also enjoy

And The Winner Is…

The Belmond Photographic Residency, now in its second year, has crowned a new winner. Meet Tara L. C. Sood and her award-winning submission.

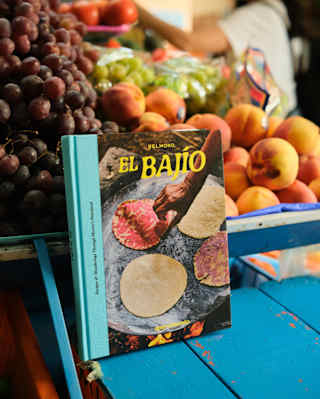

Eat Your Way Through El Bajío

Discover ‘El Bajío: Recipes & Wanderings Through Mexico’s Heartland,’ the fourth cookbook in the collaborative series between Belmond and Apartamento.

JR on the Making of L’Observatoire

The renowned French artist JR challenges traditions and sparks dialogue with his monumental artistic creations. Turning his eye to the iconic Venice Simplon-Orient-Express where he's designed an entire carriage onboard, the L’Observatoire is an artwork in motion. Transforming every detail into an opportunity for introspection and adventure, read JR in his own words as he explores the deeper meaning behind his most ambitious project yet.

How Wes Anderson Redesigned Our Train

Travel in a vintage train carriage designed by pioneering film director Wes Anderson, director of new film The Phoenician's Scheme, on your next visit to the United Kingdom.

Castello di Casole, As Seen by Cecy Young

The latest in Belmond’s ‘As Seen By’ photography series sees Cecy Young discover a sense of home in the sprawling hills of the Tuscan countryside.

Discover Belmond’s Photobooks

Inspired by Belmond’s one-of-a-kind hotels and destinations, ‘As Seen By’ is an collection of collectible photobooks with Parisian publisher RVB.

Luchino Visconti’s Tuscany

In the 1960s, Castello di Casole in Tuscany was a playground for one of the Italian film industry’s biggest disruptors. Film writer and historian Christina Newland, programmer of ‘Luchino Visconti: Decadence & Decay’ at the British Film Institute, explores the story of the Visconti brothers – their legendary parties, the glittering guestlists and the bar that honours them today.