Contemporary Sicilian Designers

Article

Shape Shifters

Of all the islands in the world, Sicily wears its sun-soaked history with the most style. But its makers and designers are now rebelling against the time-worn stories and, as Stephanie Rafanelli discovers, experimenting with edgier creations…

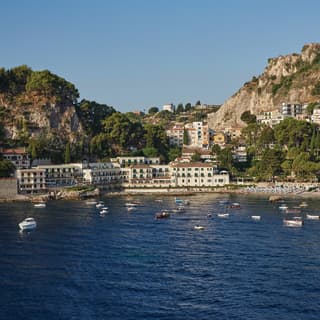

Mount Etna presides over the Grand Hotel Timeo in Taormina, composed as a priest in snowy robes, a waft of incense trailing into the sky. The creator-destroyer of Sicily has many guises and at dusk it fades out, transparent as a ghost. Over 200 eruptions have lit up eastern Sicily in a neon mohican of lava, burying nearby Catania a total of 17 times. But resurrections have sprung from its slopes; newly planted vines blossomed in ashy soils; new seats of civilisation carved from its basalt and chestnut woods, baked in clay and cast from iron ore.

The era-glorifying designs of the Magna Grecia, the Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Normans and the Spanish Baroque left Sicily with seven UNESCO Heritage sites; and Sicilians as custodians of ancient ceramics, masonry and woodwork traditions. After Italian unification and the devastation of the World Wars, the island escaped much of the industrialisation of northern Italy. And today some of its master craftsmen are official ‘Living Human Treasures’, their time-worn hands considered dusty relics. Of those who have carried forth their family’s flickering torch, many have turned to Sicily’s tourist boom to survive, churning out the beloved tropes of the Sicilian Baroque: majolica plates with curling waves of golden sunlight, ceramic Moor Heads adorned Carmen Miranda-like with fruit, and wooden curios decorated like merry-go-rounds by the island’s dying breed of cart painters.

But now a crop of pivoting studios are turning their backs on nostalgia, and re-casting their island’s heritage and classical architecture with high-end handmade contemporary design.

MEET THE CONTEMPORARY SICILIAN ARTISTS

In Messina province in the far north east, the daisy-strewn ruins of Tindari look out to the Aeolian Islands through a hazy visor of blue. Nearby, at a workshop in Patti, an ancient area of masons, three pairs of hands sandpaper a stone table that looks like a Palaeolithic altar rounded by waves.

In the last decade, Patrizia Furnari and husband Fabio Fazio, both architects, have transformed her father’s marble tile company into innovative Sicilian stone interiors brand Lithea. They commission young local designers, whose experimental ideas are realised in equal part by advanced technology and ancient stone craft techniques.

“Stone is a living fossil: nature’s work of art, thousands of years in the making. Each piece is unique,” says Furnari, who has the knowledge of a petrologist from being around marble craftsmen as a girl. “Sicily is a marvellous world rich with references and raw materials; each region has a different stone: Etna’s lava stone, Syracuse’s white limestones, Palermo’s marble. We wanted to distinguish ourselves as Sicilian designers telling the story of our island through our history and materials but in a very different way.”

In one collection, the weave of traditional Sicilian embroideries were blown up and transposed on hand-finished marble tiles. In another, Roman mosaics and church marble inlay were re-envisaged into stone tables and patterned bas-reliefs like lithic jigsaws, brushed with copper leaf by a veteran Palermo art restorer. Satellite images of the island of Pantelleria were the starting point for last year’s earth-coloured designs. Furnari believes there are “the beginnings of a new Mediterranean design movement in Sicily, with brands like us differentiating ourselves from the minimalism of Milan and northern Italy.”

Even Val di Noto’s eight UNESCO-protected Sicilian baroque towns, rebuilt in the ‘new’ style after the cataclysmic 1693 earthquake, offer unlikely contemporary cues. Beneath the wedding cake-like joie de vivre of belfries and pot-bellied balconies are geometric city plans, tricks of light, spatial awareness and mono-coloured stone palettes.

It was in this context of elegant maximalism that new Sicilian furniture brand Not.O was founded by entrepreneur Felice Rizzotti, of Catania’s famous Rizzotti Design store, and Ferruccio Laviani, art director of Italian design brand Kartell. Rizzotti’s great grandfather weaved the rattan seats of Chiavari and Thonet chairs in the 1890s, the latter manufactured in Etna white chestnut wood. “My family lived through all the design revolutions in Italy,” says Rizzotti, as we walk through the mirrored ballrooms of Palazzo Biscari in Catania. “I lived through the 1980s when radical Italian design group Memphis made a bold statement and defined the times. Now, luxury products just respond to market demand, they are all so similar.” His ambition was to “found a handmade high-end brand with the presumption to be different from a Sicilian point of view.”

Laviani, already saturated with regional iconography through his design of Dolce & Gabbana’s stores, set about freeing up the notion of Sicilianità [Sicilian-ness]. The pair went through three years of meticulous research, tracking down cabinet makers and artisans capable of applying traditions to new ideas. “It was a continual process of trial, error, and rebound. When you do something different, you need to find the artist amongst the artisans.”

Laviani re-channelled 18th-century wooden inlay through the prism of the 1930s Futurist murals of Benedetta Cappa Marinetti at Palermo’s Post Office. The result: a five-wood marquetry of 45-degree triangles in the muted tones of Piazza Armerina’s Roman mosaics. Other cabinets were hand-painted: by a church window restorer on screen-printed glass; by a specialist in UNESCO-protected Sicilian puppet theatre; and by the ceramicists of Caltagirone.

Orografie, founded by entrepreneurial interior designer Giorgia Bartolini in 2020, works upon the concept of ‘amphibious design’. Its re-imagined furniture for the virtual age seems to belong to a futuristic Catania.

“The world is going in a hybrid direction that has modified our behaviours. But design objects in the last decade haven’t responded,” says art director Vincenzo Castellano. “With the concept of ‘glocal’, we wanted to show that a brand from an isolated area beneath Mount Etna can think about the human future and that, ‘handmade in Sicily’ [shouldn’t mean] closing oneself off in the stylistic features or folkloristic references of your region.”

The Sicilian quotient lies in the making, harnessing local materials and craftsmen from Catania, Ragusa and Modica. “That was fundamental,” says Bartolini, her suede boots caked in sawdust as she shows me around the workshop of bespoke furniture makers Exedra. Everything the colour of honeycomb in the afternoon light, 44 expert hands – “all irreplaceable” – carve ornate chair legs and intricate beechwood inlay in a complete artisanal line of production.

The leaf shaped ‘Tavo’ tables were handcrafted here in layered white chestnut and oak: a series of low modular surfaces of different heights. The tables were the creation of Catania-based studio Giuliano Fukada – one of a mix of designers given the brief for Orografie’s first collection; a mix that ranged from big names to Sicilian studios and young digital natives. Another series of fIve upholstered benches in white chestnut at varying angles, multi-tasks as a Pilates gym, and/or writing, eating, lounging area. “The design anticipates the new rituals and postures of our age,” Bartolini explains. A stand, like a wooden prayer pew, functions as a hair drying and social-media scrolling prop, a hanger, a bedside table… An orange pottery centrepiece has a triple personality as a vase-candlephone deposit “that gives dignity to our iPhone,” laughs Castellano.

Outside winds often blow in change. The ceramic Moor’s Head, as weighed down as Medusa’s by flourishes and caricature, has recently been streamlined for contemporary tastes in single jewel-tone glazes, by two childhood friends from Caltagirone, architect Davide Filia and former journalist Livio Rizzo, who co-founded Crita Ceramics (with another friend Mattias Scheiber) in 2018.

The legend of a girl from Palermo who decapitates her duplicitous Arab lover and plants basil in his head is part of the local anthropomorphic ceramics tradition, along with cyclops motifs – once inspired by the mysterious ‘one-eyed’ skulls of dwarf elephants. “Traditional Moor’s Heads have these really beautiful Central African features, but the Moor was a soldier from the North [around Syria],” says Filia. Crita tempered their mutual love of the Baroque – “it doesn’t mean overdecoration” – with Nordic clean lines and a little cultural realism, giving life to a striking Arabic lothario, named Soloman. “We took everything off , added more North African features, a long neck and an elegant turban inspired by Titian’s Suleiman the Magnificent,” explains Rizzo, surrounded by glazed milk-white heads.

Elsewhere, dynamic insiders Nicolò, Fausto, and Alessandro Parrinello are not only building on the work of their father – a veteran ceramicist who pivoted to contemporary design with Made A Mano in 2001 – but carrying forward pottery into the future. In 2019, they founded Ninefifty (the degrees centigrade at which glazes transform in the kiln), a name that speaks to their advanced technical know-how with ceramicised lava stone learnt from early childhood. “We’ve spent our lives covered in dust,” says Fausto from a vast compound, like a modernist craft utopia. Here the wobbly surfaces of tiles are painted freehand in muted clay and ink tones with primordial symbols designed or beautifully scratched like petroglyphs.

Their Alphabet collection, a 44-tile series of abstract signs on display at the ADI Museum, won Best New Product at EDIT Napoli 2021 and has been nominated for a Compass D’Oro (the oldest and most influential design award). But the brothers will leave more (and less) than other experimental designs to Sicilian posterity. A zero-waste company, they have developed non-toxic glazes; donate their rejects to the Ministry of Education; and are researching scientific methods to recycle volcanic dust pollution.

Electric brands like Ninefifty are restimulating the heart of Sicily’s creative culture; but the closure of craft-teaching bodies and an exodus of young Sicilians still threaten its lifespan. “We’ve lost much of the new generation to tourism,” says Riccardo Scibetta, the founder of Palermo’s MYOP design project. Exalting the domestic Mediterranean symbols of his youth, Scibetta pairs artisans with designers, composers and writers, and created black-and-white photographic ‘backstories’ for the resulting made-to-measure pieces. Marantò, a room divider made by his family’s metal-working business with hundreds of brass pipes, elevates the Mediterranean’s ubiquitous fly blinds into a sensory art installation.