Holy Mountain

Holy Mountain

Mountains are an incredibly important symbol in Incan history and Andean culture — both geographically and culturally. Join us as we climb through the history of the Andean mountains, learning how indigenous people are maintaining ties to their natural and spiritual surroundings.

Andean locals believe that the mountain range they live on, farm, and worship is a magical gift. It is a life’s dedication to a meaningful connection to the land beneath their feet that few other cultures could lay claim to, with indigenous families maintaining centuries-old traditions to this day. Jagged mountainside terrains offered soil for the Andean community to develop their agricultural ingenuity, with terraced farms climbing high up the hills; unto these mountains they bequeathed offerings, sending love to the gods that the mountains represent.

As the longest continental mountain range in the world — stretching through seven countries and up to over 22,000 feet — the Inca civilisation believed that the Andes were their portal to the gods. Many to this day still consider these mountains to be an important, life-affirming link between their mortal selves and the powerful forces that bless them with fortune.

Apu is the name given to mountain spirits in Inca culture. Meaning ‘lord’ in the Quechua language, apus were believed by the Inca people to be active, protective spirits responsible for the success of livestock and crops, as well as watching over the communities living in the valleys below. One of the most famous in the Andes is Salkantay, a popular trekking alternative to the more touristic area of Machu Picchu. Today, an early-morning drive from Cusco into the Sacred Valley will give you a stunning glimpse of Salkantay’s heft and power. As its snow-capped peak – the highest in Cusco’s Vilcabamba mountain range – rises majestically over the sleepy city, it’s easy to see why so many consider this natural marvel to possess an inherent magic.

Its Apu is only second in importance to that of Ausangate, a 6,384m beast that attracts thousands of pilgrims each year for the annual Quyllur Rit'i, or ‘star snow’ festival, which often involves a six-hour hike to reach. Together, Salkantay and Ausangate – who are considered to be spiritual brothers – form the two most important apus in the Cusco region, while Veronica mountain is considered to be the ‘protector’ of the Sacred Valley.

The deification of Peruvian mountains did not cease when the Spanish conquered Cusco in 1532, however. In fact, the curious melding of Christian and pre-Columbian beliefs is visible in Colonial-era artwork, much of which is on display throughout Monasterio, A Belmond Hotel. Conquistadors were keen to inhibit the worship of indigenous idols, seeing them as pagan and ungodly and instead, spread the word of Christianity throughout the city. Soon, many Peruvians viewed the Virgin Mary as an incarnation of Pachamama, the Earth Goddess. Artists in Cusco combined Christian iconography with their own ideals of godliness, resulting in intriguing art which depicted Mary in the shape of a pyramid-shaped ‘divine mountain’ – a cultural syncretism that exists to this day.

A striking sense of mysticism resides within the Andes. The palpable, powerful spirituality lives in the dizzyingly large slopes and protects the valleys below. It looms over the mountain peaks and sites, once the stage for sacrificial rites. Throughout all seasons and tremors in Peru, the mountains stand tall and proud, certain of their power. From the imposingly magical Huayna Picchu that overlooks the famed citadel to rainbow-striped Vinicunca mountain, to visit Peru is to be blessed with endless craggy beauties to marvel at, each with its own unique story to tell.

Delve deeper into

You might also enjoy

And The Winner Is…

The Belmond Photographic Residency, now in its second year, has crowned a new winner. Meet Tara L. C. Sood and her award-winning submission.

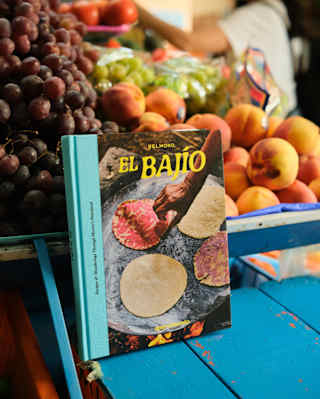

Eat Your Way Through El Bajío

Discover ‘El Bajío: Recipes & Wanderings Through Mexico’s Heartland,’ the fourth cookbook in the collaborative series between Belmond and Apartamento.

JR on the Making of L’Observatoire

The renowned French artist JR challenges traditions and sparks dialogue with his monumental artistic creations. Turning his eye to the iconic Venice Simplon-Orient-Express where he's designed an entire carriage onboard, the L’Observatoire is an artwork in motion. Transforming every detail into an opportunity for introspection and adventure, read JR in his own words as he explores the deeper meaning behind his most ambitious project yet.

How Wes Anderson Redesigned Our Train

Travel in a vintage train carriage designed by pioneering film director Wes Anderson, director of new film The Phoenician's Scheme, on your next visit to the United Kingdom.

Castello di Casole, As Seen by Cecy Young

The latest in Belmond’s ‘As Seen By’ photography series sees Cecy Young discover a sense of home in the sprawling hills of the Tuscan countryside.

Discover Belmond’s Photobooks

Inspired by Belmond’s one-of-a-kind hotels and destinations, ‘As Seen By’ is an collection of collectible photobooks with Parisian publisher RVB.

Luchino Visconti’s Tuscany

In the 1960s, Castello di Casole in Tuscany was a playground for one of the Italian film industry’s biggest disruptors. Film writer and historian Christina Newland, programmer of ‘Luchino Visconti: Decadence & Decay’ at the British Film Institute, explores the story of the Visconti brothers – their legendary parties, the glittering guestlists and the bar that honours them today.